Exit West: A Cultural Confluence

TRADITION ANd change

• • •

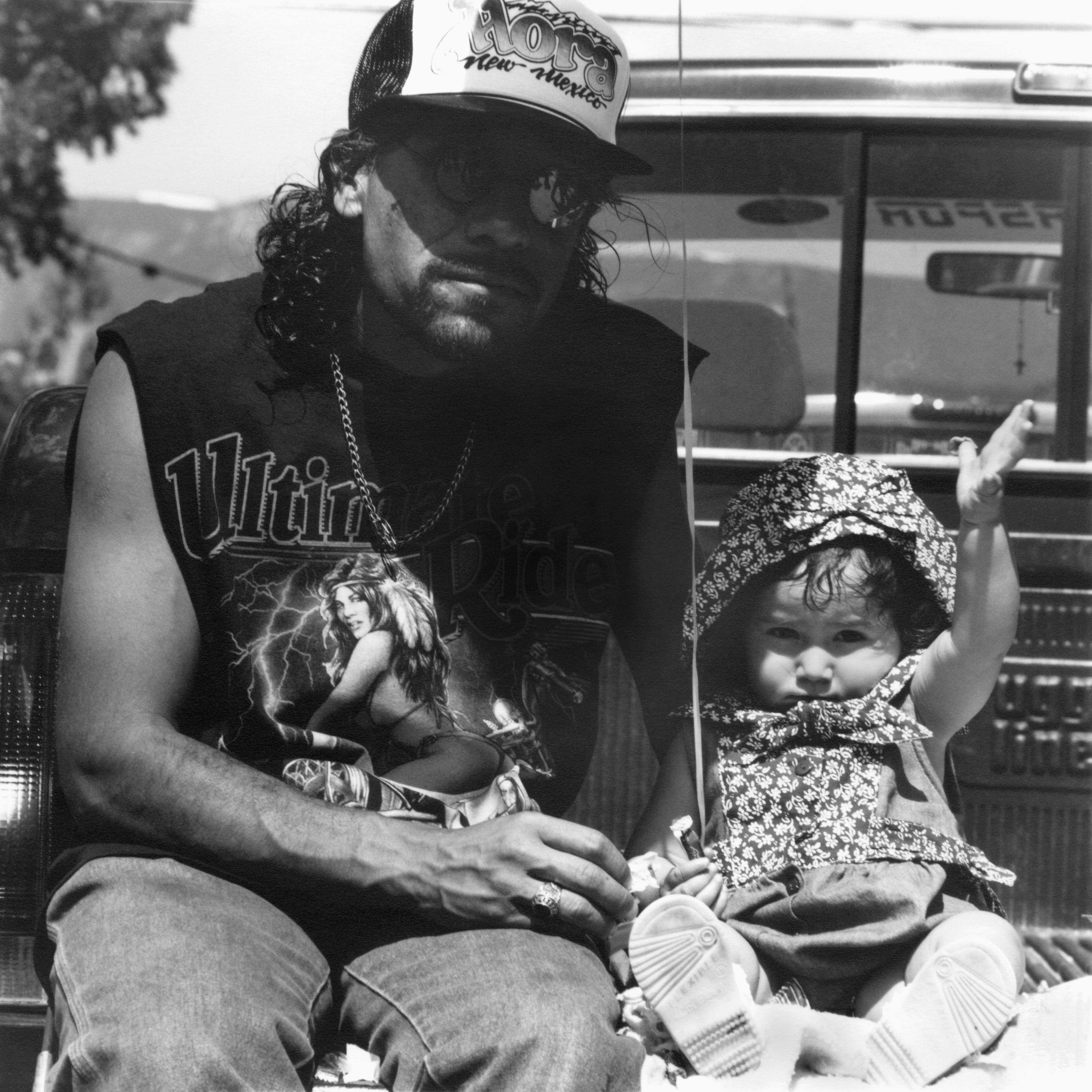

Long a land-based people, rocks, trees, livestock, wildlife, and produce continue to be harvested and sold for financial sustenance. In retiring from urban centers that provided crucial jobs, children of the valley are returning to a less complex life with renewed appreciation for their distinctive culture. And with the area attracting many drawn to its abundant natural attributes, joint contributions establishing organic farming and ranching and growers' cooperatives, the restoration of historic properties, cottage industries, and local news publications signify an honoring of the "old ways" while bringing an influx of possibility for a vibrant rural existence. It is in a visual fusion of memory, perception, and form, that these images offer contemplations on the social, economic, familial, and religious influences that continue to define the cultural landscape of Northern New Mexico.

I

Rituals & Traditions

II

Accretions of ChangE

III

People of the Valley

IV

HomeWorld

PRINTS

1994 - Present

20 x 16 Selenium Toned Gelatin Silver Photographs

Editions of 50

• • •

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

Looking Back New Mexico History Museum

Agua y Fe: Water and Faith Las Vegas, NM Arts Council and Plaza Hotel

Contemplative Landscape New Mexico History Museum

The Cultural Landscape of Northern New Mexico Office of the State Historian

Shifting Landscapes Southwest Collection Special Collections Library at Texas Tech University

From Petroglyphs to Plazas Office of Archeological Studies New Mexico Governor's Gallery

New Mexico Photographers Runnels Gallery Eastern New Mexico University

• • •

COLLECTIONS

Center for Southwest Research Special Collections Library University of New Mexico

George Eastman Museum

Harwood Museum of Art

Museum of Fine Arts Houston

Stanford University Special Collections Library and University Archives

• • •

PRESENTATIONS

Contemplative Landscape New Mexico History Museum

Where Angels Come to Sing Theaterwork

Shifting Landscapes: Considerations of Time, Place, and Culture SPE Southwest Regional Conference

• • •

PUBLICATIONS

Cheryl and Bill Jamison, Tasting New Mexico, Santa Fe, Museum of NM Press, 2012